- in Blog , Observations by David Wilkinson

- |

- 4 comments

Making organisations more effective: The problem of academic – practitioner distance

There is no doubt that our universities conduct valuable and useful research that can help organisations become much more effective. In fact they produce lots of useful research that organisations could use. As the call more more evidence based practice increases, and with good reason, a rather large problem arises. Hardly anyone outside of academia has access to the research, has the time to find it, and even if they do find it understanding it is a nightmare. There is a very real and damaging academic – practitioner distance

The problem is the gap between the organisational practitioner (manager, leader, Human Resources, Organisational Development, Learning & Development, Change agent etc.) and academia (researcher and lecturer): what is known as academic – practitioner distance.

The gap isn’t just a physical one (and this matters as I will touch on later) but there is a gap of perspective, language, understanding and thinking.

Academic – Practitioner distance

Largely we have two polarised groups with a few individuals dotted in between the two camps.

The organisational workers corner

In the red corner we have the full-time practitioners and workers in organisations. They are focused on delivering the outcomes specified in their job role as a worker or a manager, leader, sales, Human Resources, Organisational Development, Learning & Development, Change agent etc. They know what they know, have experience of working / surviving in the environment, which, let’s face it, is usually complex, political and very demanding. They talk the languages for the organisation and their profession (OrgDev, Org Change, HR etc), know what it is like to try to navigate and negotiate within the organisation. They are immersed in the day to day challenges and issues faced. They are, however, part of the culture and, as a result things, are often hiding in plain sight. Further, regardless of remonstrations to the opposite, they are subject to the pressures of the politics of the organisation and their departments / functions.

This means that values, beliefs, understandings, judgement and assumptions will inevitably be ‘nudged’ at the very least and outright skewed at the worst, often without their knowing. These are the shared, often unquestioned, assumptions and pressures that can often only be seen from outside.

The practitioner / organisational corner

In the blue corner we have the full time academics, lecturers and researchers of the organisation. They live in a world usually not grounded in or hampered by the realities and pressures of the practitioner. They do however get to view and see a world of evidence and the world of the practitioner from an outsider perspective. This can be incredibly useful, as they often see things that people embedded in the culture of the workplace don’t or can’t see. They, however, will often not be quite as objective as they think they are. They bring with them all the assumptions, thinking and perspectives of their discipline.

Be impressively well-informed

Get your FREE organizational and people development research briefings, infographics, video research briefings, a free copy of The Oxford Review and more...

As mentioned, the full-time academic does usually have a lot of research evidence and overview as opposed to practitioner evidence and folk-lore at their disposal. This perspective can be incredibly useful to the practitioner.

The inbetweeners

Then there are the inbetweeners in the problem of academic – practitioner distance. The people like consultants, practitioner-academics – people who are, or recently have been, practitioners but are now pursuing academic studies or an academic career, consultant-academics and (a few) ex full time academics, who are now either consultants or practitioners.

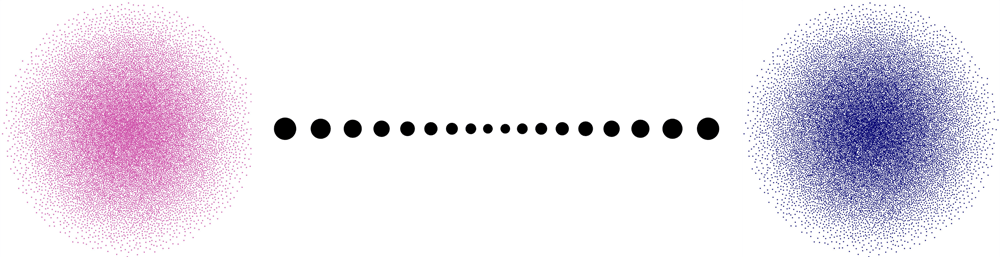

When we look at a plot of the people in the evidence-based mix it probably looks like this:

Research and reality

The issue here is that the people with the more pure forms of objective (-ish) evidence are in academic institutions and the people with the grounded know-how of the realities are in the organisations, with a few bridging the gap.

Both camps in the issue of academic – practitioner distance have their own language and understanding of the world. The academic language is often precise, particular and striving to disambiguate. This is often seen by non-academics as impenetrable jargon. Every discipline (Psychology, Medical Sciences, Physics etc.) has its own language, nuances and peculiarities, based on the current understanding and history of that discipline. For example the term “Valence” in engineering means a hinged access to an engine, in psychology it means a characteristic of an emotion, in chemistry it means form of chemical bond. The issue of academic – practitioner distance is not a simple one.

The access issue

Additionally, academics have the checking mechanism of peer review for all of their work, which is normally carried out by publishing their work in peer-reviewed journals where other academics review and critique the research, its methods and conclusions for reliability and validity. The journals within which the research papers are reviewed and published for scrutiny are usually specialised, expensive and not that easy to find for non-academics. They are published in just about every country and language in the world and are often only accessible through specialised academic databases. You have to understand, in part at least, the language of the discipline to understand what to search for. However, before even this stage, you need access to the various specialised academic databases. These are frequently only accessible from universities which only increases the academic – practitioner distance.

Then you need to gain access to the actual journal and article, which again is either housed in a university library or is available online through a specialised academic portal. Once you have access you then need to understand the precise language of that discipline to extrapolate the meaning and usefulness of the research.

This not only takes skill and physical access (and often money) to these resources, but also that most precious of resources, time. Time that is part of the researchers’ and academics’ jobs, but often not that given to practitioners. Consultants are also rarely directly remunerated for doing research and spending time in libraries or online chasing down references and studies. Research, both desk research and actual field research is frequently a long term and involved process. Many studies take years to complete. A full-time PhD for example takes a minimum of three years to complete and that is just one study.

The immediate world of the practitioner

Practitioners, on the other hand, live in a more immediate world where things move fast and are at the whim of organisational rules, policies, and aims. The solutions practitioners are called on to provide need to fit with organisational cultural conventions, be understandable at least to the (often non-expert) leadership, practical in their implementation and cost effective. This means that any solutions (and that largely is what they have to be – solutions, as opposed to theories for testing) need to be available, readily understandable to a wide range of busy non-experts, practical, implementation ready and preferably successful. Any solutions also have to blend with the ‘common’ sense understandings of the culture or challenge it in a way that still makes sense.

As ever, being right and making sense from a perspective, are two very different things.

In my situation as an ex-full-time practitioner/ ex-full-time academic and current pracademic I see the academic frustration with practitioners and organisational leaders and practitioners,’ frustrations with academics, and there are precious few who sit between the two worlds translating, explaining and converting. From this position the academic – practitioner distance is all to apparent.

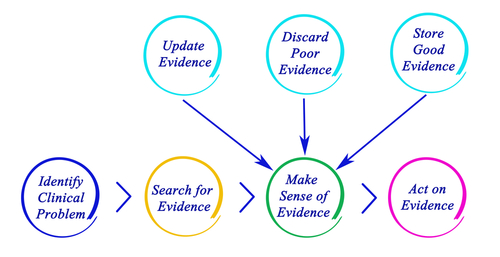

Evidence-based practice

One of the most common frustrations for academics is that not enough practitioners embrace evidence (research) based practice. This is an issue I have written about before – Why evidence-based practice probably isn’t worth it…

When you look at the industries that have successfully engaged with evidence and research based practice, like health and aviation, we find that there is little distinction between academics and practitioners. In the department I work in at Oxford (Medical Sciences Division) the lecturers are surgeons and doctors. The surgeons and doctors are doing research. The hospital is a university hospital. One feeds the other. There is no distance.

This breeds a culture where the practitioners use and engage with research and the researchers on a day-to-day level and the researchers who are not practitioners are always close to and situated in the context that their work will feed into. You can’t slide a piece of paper between them. There is no tangible academic – practitioner distance to speak of. The practitioner are the researchers and the researchers are often practitioners.

The problem in many organisations and university departments is that they are both physically removed from each other and ideologically and culturally removed from each other as well. Now I am not saying that they need to be housed in the same building, but there needs to be greater interchange between them. Businesses and organisations should have researchers, and universities should be making greater use of practitioners. They should be learning each other’s cultures and ways of seeing and doing things.

Transactional rather than transformative

All too often the relationship between organisations and universities is transactional. Universities see organisations as a potential source of funding and data, and organisations see universities as a source of external consultation and the odd research project. This is not a transformational relationship. The examples of aviation and health above are mutually transformational.

The aims of a transformational relationship are where the aim is to build mutual trust, where each side is listening and they are working to their mutual benefit to build joint engagement, involvement and commitment to the aims of both entities.

Does it matter?

Does all this stuff about academic – practitioner distance matter though? Yes actually, it really does. The best evidence for practice is often locked away in academia and the practitioners are locked away being busy in organisations. The best and most up-to-date evidence, based on good research using the very latest techniques can take years to permeate into the workplace, if indeed it ever does. We frequently find really useful and potentially game changing research that has been published in some obscure journal that hasn’t even been cited by other academics, let alone seen by practitioners.

At best, most research sees the light of day (for practitioners) when they do a degree, or a Masters (MBA etc.). However, given the sheer amount of research produced – over 78,000 papers a month, it is a lottery whether it ever gets taught on a course.

Given that most practitioners and consultants don’t have the time or expertise to find, translate and turn the research into something useful and practical it’s like we have two different universes operating next to each other, both largely ignoring the other.

Extra-knowledge management

One of the tenets of knowledge management in organisations is to ensure that knowledge, both tacit and explicit, is captured, updated and then made readily and easily available to practitioners, who have the skill and ability to do something with it. It is the very stuff of a learning organisation.

These systems need to move wider and incorporate all the useful research evidence there is in the academic system, in a systematic way and to bring it into focus in the organisation, a form of extra-knowledge management.

99% of everything you are trying to do

99% of everything people are trying to do in an organisation has already been done before and meticulously researched and understood. When I work in organisations it seems as though they are having to constantly re-invent the wheel and there is no need.

Authentic Leadership and Being Authentic – What does that mean anyway?

Be impressively well informed

Get the very latest research intelligence briefings, video research briefings, infographics and more sent direct to you as they are published

Be the most impressively well-informed and up-to-date person around...

That was beneficial for me, thanks David.

2breaking

Hi Sarah,

That is really interesting, thank you so much for letting me know and the link – really useful. If I can help at all please do let me know.

David

Hi David, thanks for this excellent article. I wholeheartedly agree with the points you are making and as a practitioner with a close interest and eye on research am often frustrated by the ‘woo woo’ which is often so well received in many organisations!

The International Society for Coaching Psychology (I am a graduate member and more recently a director) has recently established research hubs to address this exact point. I have established our first, in Cambridge, in order to “bring together coaching psychology practitioners with researchers and students to share information, knowledge and ideas in a two-way exchange of thinking and exploration”. Please do take a look – http://www.iscpresearch.org/iscp-research-hubs/iscp-cambridge-research-hub/

I am currently planning our 2018 schedule and keen to hear from researchers and practitioners.

BW Sarah