- in Blog , Research , Work psychology by David Wilkinson

How our cognitive outlook and perceptions affect our well-being – new study

Our cognitive outlook and perceptions, or how we construe things, can have a significant impact on a range of outcomes. For example, people with a generally positive outlook tend to have higher satisfaction ratings for things like relationships, family, job etc. Additionally, as you would expect, people with a more positive take on things tend to be more optimistic and usually have higher levels of self-esteem.

The new review of research has looked at how cognitive outlook and perceptions affect our well-being. In particular, they looked at construal which refers to an individual’s subjective perception and evaluation of a situation, and how it impacts well-being outcomes.

- The modal model of emotion

- What we focus on matters

- It goes both ways

- The ‘broaden and build’ impact of positive emotions

- Creating more success

- The memories we choose to focus on

- Appreciation and gratitude

- Optimism

- Self esteem

- Self-determination, autonomy and levels of competence

- Attributional style

- Ruminative style

- Conclusion

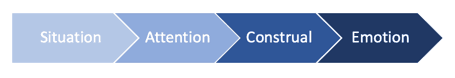

The current thinking (known as the modal model of emotion) and research has shown that there is a direct connection between our cognitive outlook and perceptions of the situation, what we pay attention to and our emotional response:

The previous research has shown that what we pay attention to and the meanings we ascribe to things (construal) has a direct impact on our emotional response to situations. Attention is seen as a selective process, where people either consciously or unconsciously decide what to focus on within a situational context. Concentrating on certain attributes within a situation tends then to lead to a certain set of perceptions, meanings or conclusions (construal) about the situation, which leads directly to our emotional response.

A recent meta-analysis of 33 studies looking at people with anxiety and depression and comparing them to people without anxiety or depression found that people with anxiety are significantly more likely to pay attention and look for threatening situations, compared to people without anxiety. Further, compared to people without depression, people with depression pay significantly less attention to positive over negative situations. People without depression spend a significantly shorter amount of time attending to negative situations compared to people with depression.

Be impressively well-informed

Get your FREE organizational and people development research briefings, infographics, video research briefings, a free copy of The Oxford Review and more...

A range of research studies over the last 10 to 15 years has found that this effect, the link between what we pay attention to (our cognitive outlook and perceptions) and our well-being, is bi-directional. What this means is that what we pay attention to has a direct and indirect impact on how we feel, and how we feel has a direct and indirect impact on what we pay attention to.

The ‘broaden and build’ impact of positive emotions

A series of studies published between 2013 and 2017 found that positive emotions broaden our awareness and ability to take in more information. This broadening effect on our cognition has been found to build skills and resources within the individual. In effect, positive individuals become more capable, both of perceiving a wider range of data of enhancing and developing their skills and thinking as it happens.

Conversely, it has been found that negative emotions tend to significantly narrow one’s focus. People with a negative frame of mind tend to focus on, and often become obsessive about, particular details and solving a narrow range of problems.

In effect, people with positive emotions tend to become significantly and increasingly more flexible, adaptable and capable, whilst individuals in a negative emotional state narrow their focus, become less adaptable and taking fewer inputs. This effect is so powerful that simply inducing a positive or negative mood through listening to happy or sad music can create this effect.

How our cognitive outlook and perceptions creates more success

A number of studies in 2012, 2013 and 2015 found that changing people’s attention and focus towards more positive information created more positive emotions towards success and these resulted in both more success and greater well-being for the individual.

The memories we choose to focus on

There also appears to be a link between which memories we attend to and our well-being. People who focus more on positive memories tend to not only feel better, but also to have better well-being outcomes compared to people who focus on negative, sad or pessimistic memories.

A wide range of studies have found that people with higher levels of gratitude and appreciation tend to have significantly better well-being outcomes, as well as sustainable positive emotions. In particular, two longitudinal studies in 2008 and 2013 found that people who were asked to perform an act of appreciation or gratitude a day (such as writing a letter of thanks to someone they felt gratitude towards) had significantly better well-being outcomes than control groups, who did not carry out acts of gratitude or appreciation. These studies were conducted over 3 to 4 months.

Additionally, studies have found that acts of gratitude and appreciation increase a sense of connectedness, boost prosocial behaviour, increase organisational citizenship behaviours and increase levels of competence.

A recent meta-analysis from 2013 which looked at 50 studies across 19,831 participants found that optimists are significantly healthier and more psychologically resilient than pessimists. Further it was found that optimists have better life satisfaction, cope with stress better, recover from surgery faster and live longer.

A number of experimental studies where people were randomly assigned to a control or ‘optimism’ group (invited to imagine their “best possible selves”) had better well-being outcomes compared to the control group.

Studies in 1996 and 2011 found that pessimism significantly increases depressive symptoms over three years. Again out cognitive outlook and perceptions at play creating a direct impact on our heath.

“…there are three primary determinants of well-being”

Self-esteem or our overall evaluation of our worth and respect for ourselves are significantly more productive and creative than people with low levels of self-esteem. Wide range of studies conducted between 2003 and 2012 found that there is a strong correlation between self-esteem, life satisfaction and well-being outcomes.

A number of recent studies (2014 and 2017) have found that a number of exercises and interventions such as self-affirmation exercises (e.g. saying to yourself on a daily basis “I am a good and moral person”) has a positive impact, both on an individual’s level of self-esteem and well-being outcomes. However, these studies show this effect is transitory, in that it only appears to last as long as the exercises and affirmations are being conducted.

Additionally, a number of medical studies have found that negative views of oneself predispose the individual to depressive symptoms. Studies in 2002, 2003 and 2012 found that consciously focusing on and attending to positive construals of yourself (actively looking for and paying attention to positive feedback and positive portrayals of oneself) not only increases self-esteem, but also has a positive impact on well-being outcomes.

Self-determination, autonomy and levels of competence

Studies in 2000, 2001 2010 and 2011 found that there are three primary determinants of well-being, all of which fall under the broad heading of self-determination:

- Autonomy

- Competence

- Connectedness

Autonomy refers to the level of ability an individual has to govern themselves, control their outcomes and be independent.

Competence refers to their general levels of knowledge, skills and abilities in any particular situation. The higher their abilities to be able to control a situation, as well as their belief in their ability to be able to control things around them (self-efficacy), the better their well-being outcomes.

Connectedness means an individual’s ability to relate to and connect to other people and groups of people. The level of connectedness an individual feels with others and in society in general is a strong correlation with both feelings of self-determination and well-being outcomes.

When an individual has a sense that they have autonomy, competence and connectedness, studies have found they also have a strong feeling of control about their lives. Three primary things that impact our cognitive outlook and perceptions

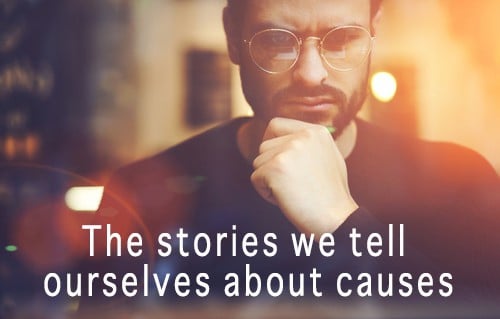

An individual’s attributional style refers to the way in which they ascribe, attribute or credit causes to events. The type of explanations we use to describe causal events has a significant impact on our well-being, flexibility, levels of persistence and productivity/success.

For example, someone who fails an exam and puts this down to their own lack of intelligence or stupidity is significantly more likely to give up and create the belief that they are unlikely to succeed henceforth.

There are a number of different types of attributional style that have a direct impact on the outcomes for an individual:

- External versus internal attributions or explanations. Does the individual think the cause of an event was because of something they themselves did or are doing or because of some external power? Internal attributions include things like ‘I didn’t do enough studying’, ‘I’m not intelligent enough’ and the likes, whilst external attributions are explanations such as ‘the exam was unusually difficult’ or ‘I walked under a ladder before the exam (superstition)’, for instance.

- Stable versus unstable explanations. Examples of stable attributions include ‘I’m not good at exams’, whereas an unstable explanation would be ‘I didn’t prepare adequately for this exam’. As can be seen from these examples, stable attributions are more concrete and don’t allow the individual to change the trajectory of the outcome whereas unstable attributions allow the individual to take control and change the outcome. Stable outcomes tend to be seen as a permanent state of affairs.

- Global versus specific attributions.Global attributions are explanations that suggest that the cause of the situation is likely to apply to all other similar situations, whereas specific attributions confine the effect to the particular incidents in question. Someone who explains things using global attributions might believe that failing an exam is indicative of their general level of success in life and think that they are the kind of person who just doesn’t succeed at things. People who tend to use specific attributions, however, tend to believe that failing an exam is an isolated incident and they have control and the ability to be able to change future outcomes.

It turns out that, using internal, global and stable attributional styles, decreases well-being in negative situations but increases well-being in positive situations. Whilst it is not entirely understood why this is the case, a study in 2011 found that people who ascribe internal, global and stable explanations to negative situations tend to suffer from learned helplessness. Conversely, people who tend to use internal, global and stable explanations in positive situations tend to have what is known as ‘learned optimism’.

These ideas of learned helplessness and learned optimism are key to understanding how people construe events around them and their ability to be able to cope and deal with them and appear to be both a direct result of our cognitive outlook and perceptions and also change our thinking and perceptions.

Ruminative style refers to the tendency to focus on thinking about the symptoms, causes and consequences of distressing and negative events, rather than focusing on finding solutions to the issue. A range of studies over the years has shown that people who tend to engage in negative rumination are significantly more likely to develop depression and have longer periods of depression.

Further, it should be noted that rumination is the focus on past events and negative rumination tends to focus on past negative events. Negative rumination is strongly associated with internal predictions of negative future outcomes, whereas positive rumination tends to be connected with expectation of positive future events and outcomes.

This meta-analysis is useful in that it pinpoints a range cognitive outlook and perceptions (together known as Implicit Cognition) that have a direct impact on our perceptual capabilities and well-being outcomes. Further, some of the factors such as we pay attention to and focus on also has a direct impact on our levels of success.

Members go to the Membership site > Library > Archive > search for “perceptions affect” to download the full research briefing and reference

Not a member?

Apply to join now and get:

- Weekly research briefings sent direct to you every week

- A copy of the Oxford Review containing between twelve and sixteen additional research briefings every month

- Research Infographics

- Video research briefings.

- Special reports / short literature reviews on topics that appear to be getting a lot of research attention or if there has been a recent shift in the thinking or theory

- The ability to request a watch list for new research in keyword areas (as long as it is within the realms of:

- Leadership

- Management

- Human resources (not legal aspects)

- Organisational development

- Organisational change

- Organisational learning

- Learning and development,

- Coaching

- Work Psychology

- Decision making

- Request specific research / brief literature reviews

- Access to the entire archive of previous research briefings, copies of the Oxford Review, infographics, video research briefings and special reports.

- Access to Live Reports – continually updated as new research on the topic is released

- Members only podcasts – research briefings in audio – coming soon

- Live continually updated reports

Be the most up-to-date person in the room

Apply to join now

Be impressively well informed

Get the very latest research intelligence briefings, video research briefings, infographics and more sent direct to you as they are published

Be the most impressively well-informed and up-to-date person around...